Donald MacLean's Blog 2

COMMUNICATION

Cousins are asleep in other rooms. Including two girls, the same ages as my brother and I - they speak only Spanish - having arrived at Shotley Bridge from Bilbao in an interesting car driven by their father who is Chief Engineer of the Rio Tinto mines.

Granny Heron has a bulldog called Teddy who has won rosettes at County shows. Family folk-lore includes two stories about him:

A visiting vicar, shown by a maid into a sitting-room and innocently sitting in Teddy's armchair was joined by its owner who climbed behind him, pressed four sturdy feet against the chair-back and evicted the intruder firmly onto the floor.

My mother and father had met for the first time in 1925 at the house of mutual friends in London. They persuaded their hosts to go out for a meal, leaving them to baby-sit for the evening. When the other couple returned my parents-to-be were engaged! When Mary took her fiancé to meet her parents Teddy, detecting the scent of Cairn puppies on the newcomer's shoes, naturally replaced that with his own signature! Major Kenneth, a dog-breeder himself, made light of the incident and was accepted warmly into the Heron clan.

There are, at Shotley Bridge, two rooms which are off-limits to children. The door of a gloomy 'morning-room' is rarely opened and, when it is, the interior is obscured by a heavy curtain on a rail behind it. The other sanctum-sanctorum is up a narrow flight of stairs - Grandpa's workshop.

One day I pluck up the courage to ask him about it. He doesn't reply, just smiles ... and

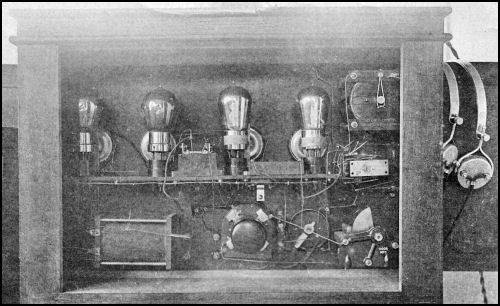

leads me up there ... into a wonderland of mahogany cabinets ... whose lids he raises to reveal coils and condensers and glowing valves, and above them the horn of a loudspeaker from which comes a foreign voice. The cutting-edge of 1930 technology – the magical world of wireless!

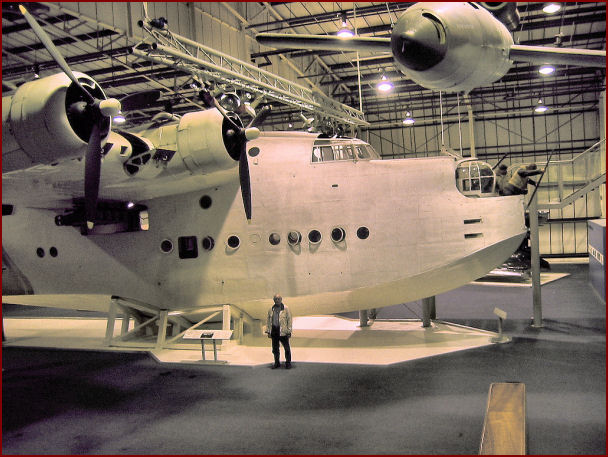

In Oban bay, as 2,000 gallons of petrol

are being pumped into the wing tanks of the big flying boat, the wind is rising

ominously. It takes all the skill of our experienced (21-yr old) pilot to

get our 29 tons up and planing over the chops, and then airborne. The interior of the Sunderland is spartan. Even with my 'Biggles'

helmet and its earphones, the steady thunder of four big engines, hour after

hour, numbs my brain and I have to fight to understand the operating manual of

the '1154/1155' radio system in front of me. I'm still in training

as an RAF pilot and had wangled my way onto this Atlantic sortie, very

unofficially, when its crew of nine lacked a wireless operator. No-one

mentions the probability that it will be too rough to land on our return (God

Willing) 10 hours later. Completing our mission … just getting back … is

challenge enough.

TWO MUSEUM PIECES

Sunderland and me, 60 years later,

at the RAF Museum in Hendon.

Within weeks the Air Force announces that no more pilots are needed. I transfer to the new technical corps of the army, REME, to spend three years acquiring, then teaching, the skills involved in maintaining the equipment with which London communicates with its embassies and army commands worldwide.

I had to sign the Official Secrets Act - like the now-legendary code-breakers of Bletchley Park (which has become a museum of which I'm a proud sponsor) - and then acquire a wide range of very disparate skills – from de-coking 3-ton Lister generators, through powerful broadcast transmitters and aerials, to adjusting secret cipher machines with a magnifying-glass and tweezers. When trained, and eager to be deployed to a glamorous posting in East Africa, perhaps even Washington, I am instead retained to teach the next (and final) generation of our successors. (In the further interest of secrecy our numbers were severely limited and, as I was to discover to my chagrin, our release back to civilian life was to be repeatedly postponed.)

It's 1947. On a corner table sits a somewhat dented short-wave station. Newly 'ex-service'. Like me. The voice which comes from it speaks English but with an unfamiliar accent. The voice sounds elderly, congratulating me on my new job at the local BBC studios, on my new transmitting licence "GM3DNQ", and on having the good sense to find a nice wife willing to share her husband with his intrusive hobby. Margaret and I are in our bedsit in Aberdeen, my new friend is on his farm - in New Zealand.

In 2009 my home is full of 'wireless'. Apart from our 7 broadcast receivers and my 'ham' radio station, our 2 mobile phones are radio transceivers. So are our 7 'cordless' phones - 2 of which optionally connect with the internet (so I can talk to N.Z. for free). A pc and 3 laptops all talk to each other and to the internet by radio. 3 of our clocks are synchronised by radio with an atomic clock in Cumbria.

A little screen by my armchair displays, wirelessly, all the measurements from a weather unit in the garden. Even the bell-push at the front door connects by wireless with the 'doo-loongs' in the kitchen and Ann's study. All of this will be everyday stuff to my grandson ... how on earth do I convey to him the exhilaration of that 1947 conversation with New Zealand?

Communication.

My job. My hobby.

In 1947 my salary was 28 shillings (35 cents) a week. It being an austere post-war world this sufficed … provided we walked everywhere and rarely indulged ourselves by swapping the gas-pipe of our single cooker-ring over to the tiny gas-fire. My parents came to visit us. From the little dormer window I watched the Lanchester park at the curb, chauffeur Bellamy emerge, immaculately uniformed, to hold the rear door open for my parents.

They seemed strangely large in our wee attic room, praising the few personal touches we had achieved and hugging us both when they departed. It wasn't until Margaret later remarked on it being typically kind of them to show nothing but approval of our meagre surroundings that it even occurred to me that they could have done anything else. I was proud to be head of my wee household and expected them to be pleased. How easy to take our parents for granted!

I wonder if you happen, like me, to treasure a childhood copy of “Wind in the Willows”? I cry easily … always have. I can read the chapter called “Dulce Domum” only when no-one is watching. (Little Mole, walking in the woods with his wealthy friend, after months of living an upmarket life with him, passes the entrance to the humble home he had left. He is too ashamed to mention it, but Ratty senses the situation, insists they go back and visit it, and bustles about, lighting a fire and saying it is just the nicest, homeliest home he has ever seen.)

Towards the end of a year at Aberdeen I apply for a junior producer post in Glasgow and get it. At 22 the BBC's youngest radio producer. (For most of my career thereafter I take another step up the ladder every three years.)

One of my first big challenges is to produce for Scottish Home Service the John Buchan stories whose hero is Richard Hannay. I try the experiment of not casting anyone in the role of the second hero, Peter Pienaar … providing merely a succession of pointers to his bravery, his kindness … allowing each listener to build his/her own mental image of the great man ... never hearing a particular voice to conflict with that ideal. I tried to explain this to my experienced colleagues at the Thursday “Programme Board”. Several of them ridiculed this as precocious nonsense - very few of them thought it would work.

The audience for the final episode exceeded 30% - a record! Almost 1 in every 3 members of the nation's population including babies and those too old or too deaf (or too drunk … it was Setterday nicht, ye ken). These were, as I have said, austere days … listening to the 'wireless' was the primary entertainment. I'm told that the 'pointers, only' technique was fashionable for quite a while afterwards. I tried it later in TV but it was less effective – a listener's imagination is more engaged than a viewer's.

Communication. My distilled word number 2.

D.H.M.

"The most important thing in communication

is to hear what isn't being said."

Peter Drucker

- - - - - -

Back to 'Contents' table

On to Blog 3

- - - - - -