Donald MacLean's Blog 6

PLACES continued

(1934/1980)

"In 1934" wrote my

father "Rowntree was expanding rapidly - including the

acquisition of a number of biscuit companies. The work of all directors

was re-organised. I was invited to take the primary role in the new

biscuits division, with directorships on several boards, and taking up

residence in Glasgow."

|

|

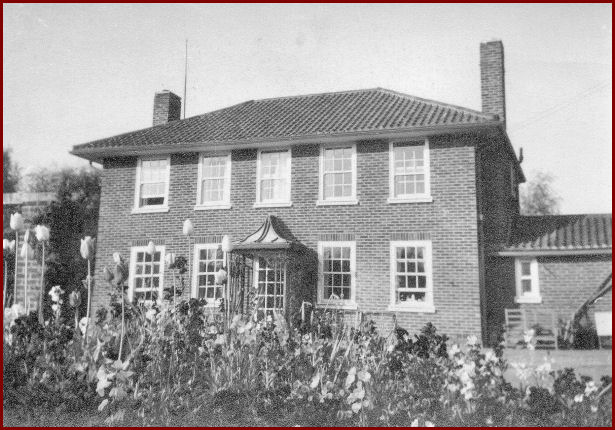

1934 Pollokshields, Glasgow |

Our new home had been the residence of Lord Provost Montgomery

- the gateposts had ornate wrought-iron lamps to signify this fact.

On our arrival these were promptly removed by City engineers

to signify the place's demotion.

|

|

2009 More trees. Still no lamps |

This was to be our home for a decade - much longer

than we had stayed anywhere previously.

My brother and I were enrolled in Craigholme, a local prep school - with brown blazers of which we were deeply ashamed (going there on our first day we hid on the floor of the car so that no-one would see us). Sister Deirdre was 1 year old.

Our home overlooked Maxwell Park - which had an L-shaped pond where we sailed our model boats. On Saturday mornings men came with model hydroplanes, powered by loud petrol engines. These exciting machines were tethered, one at a time, by a long cord to a pole in the middle of the water, round which they blasted in a great circle, very fast, skimming the surface, until the owner, in waders, flipped an extended switch as it passed. Officials had stop-watches. The object was to fine-tune your machine to minimise the time it took to make three circuits. Occasionally one of them would take-off and perform a dramatic reverse-somersault.

In the 1934 picture you will see the front windows of the Billiard Room - at the top of the house - and there was an identical dormer-type window at the rear. I dared brother Nigel to follow me climbing out of one, over the roof, and into t'other one. In the bowels of the house the phone rang - unsurprisingly a horrified neighbour shouted at our mother to get her lunatic offspring back into safety. I was summoned to a spare bedroom (whose furniture was a distinctive figured-walnut). In a drawer of its dressing-table lived a leather implement - a memento of a parental safari in Africa. Mama and I had a very grown-up conversation about risk-taking and the exemplar-responsibilities of elder brothers ... the discussion concluding with the advice that I grip the two 'claw-and-ball' posts at the foot of one of the beds for the next few painful minutes. Forty years later Ann and I spent a weekend with Nigel and Miriam in their hillside home in the North of England and were shown into a bedroom ... furnished with family heirlooms ... in a distinctive figured-walnut.

Every Thursday evening, pre-war, one of Dad's friends would visit to play snooker. He was a famous doctor - his Bentley was a gift "from a grateful patient", Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. (There was a hint of significance in the fact that the doctor's wife and our father had been friends in pre-nuptial days.) The ladies watched from armchairs on a raised dais which enabled a view of the green-baize field of battle. The most interesting item to us children was a speaking-tube, by means of which refreshments were summoned via a similar fitment three floors below in the kitchen. To attract attention you removed a whistle/stopper and blew into the mouthpiece - whereupon the similar whistle/stopper sounded below-stairs and a white ivory peg protruded to indicate which of several tubes required attention. Tea-things, decanters and glasses then travelled up to the eyrie in a 'dumb-waiter' - a goods-elevator (which, I can report, was only just too small to encompass a hard-pushed younger brother.)

At the other end of the Billiard Room was our electric train layout - on a hexagonal table with a central opening, especially built for us by our friend 'George-the-Joiner' from the biscuit factory. The locomotive was an "Eton" class - in the green livery of England's 'Southern Railway'. (In York, my friend Kenneth's trains had been in the brown of London's Metropolitan Line - which now runs in a deep cutting beyond the far end of our garden as it approaches its Northern terminus.)

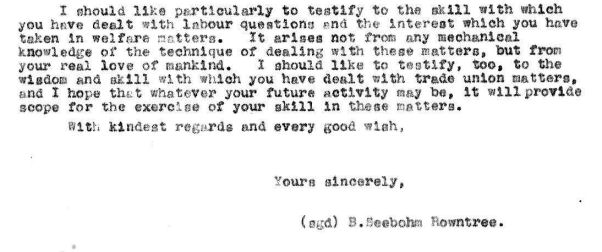

My father's Chairman, Seebohm Rowntree, was one of the pioneers of modern industrial relations and so I hope you will allow me some pride in this final paragraph of a letter which Dad received when he left Rowntree in 1944:

|

|

1944 tribute from a legendary industrialist |

I mention this now because the tutor who came to our home on Saturday mornings to give Nigel and me lessons in wood-working (in Dad's basement workshop) was the aforesaid George-the-Joiner ... who just happened to be the factory's senior Shop-Steward.

At Skelton, in summertime, a man had occasionally cycled up to the house on a three-wheeled ice-cream cart which had "Stop Me & Buy One" painted on it. At Maxwell Park, his equivalent was 'Dan-the-ice-cream-man'. His pitch was a leafy corner of the park at a road junction. His English was limited, and was interspersed with rapid streams of Italian. He was our friend. We had long, earnest, conversations.

|

|

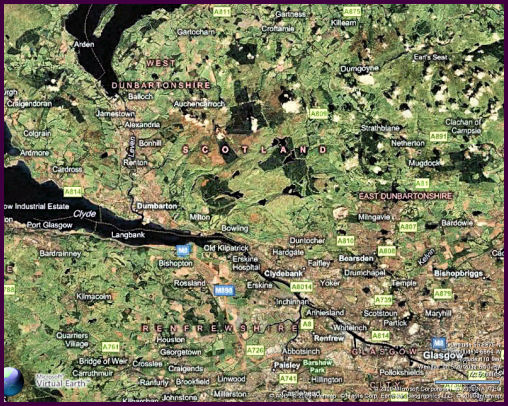

Lodge on Inchmurrin Island, Loch Lomond |

Our parents also had many new friends - including a farming

family who bought an island and moved there. They had two

sons the same ages as my brother and me. Their home was Inchmurrin

("inch" is the Anglicised version of the Gaelic word for island - "Innis").

This is the largest island on Loch Lomond, Scotland's largest inland water.

We rented from them this weekend-home - a one-time royal hunting-lodge,

which had been modernised.

This was a good arrangement. From home it was an

easy drive, across the River Clyde (using a chain-driven

ferry) at Erskine, thence to Arden on the shores of Loch Lomond - from where one of the two boys

would come in an outboard-powered boat to collect us. That frequently

took a great deal longer than the drive from Pollokshields - it depended how

long it took for anyone on the island to notice the white blob on the

mainland which we created by opening a pair of shutters on a boathouse.

And then whether anyone was minded to make the trip at the time!

|

|

Pollokshields

(bottom, right) |

I have two main recollections of our summers

there: One was relief at getting our boat back to the jetty (from which the

above

photo was taken) when the loch had produced one of its specialities - a

near-gale-force storm appearing without warning from a cloudless summer sky.

The other was being asked to fetch a tray of refreshments out to that lawn by

the water's edge for my mother and her guest (ex PT-college friend) when they

were ... er ... maximising their intake of vitamin-D in the sunshine.

They were wholly relaxed - as I tried to be - and they exchanged quiet smiles

as I retired blushing from the scene. (How much more scope my late

mother and her friends would have nowadays for their alternative-diets and

therapies.)

In 1939 our summer was spent in a small farmhouse further North near Arisaig, and with the war imminent we stayed-on there (like other 'evacuees' throughout the UK) for several months and, come September, enrolled in the one-room village school. Here a dramatic milestone in my life took place, which I shall describe in a future blog.

The single-track railway to Scotland's Western Isles

runs along that beautiful Western shore of Loch Lomond. One year the

railway company created a "camping-coach" and parked it in a scenic siding

further up the loch at Ardlui. We hired this coach for its first week. One of my chums,

George Barrie, and his family were persuaded to join

us. Papa Barrie owned the country's premier lemonade brand of the time - and a

Studebaker, the first American car we had seen. My brother and I sat

wide-eyed in the back while George, the large steering-wheel towering above him, proudly

catalogued the car's advanced features.

|

|

|

My mother and father drove, respectively, a Wolseley "Wasp" and a Humber 16/60. In 1939 the latter was equipped with one of the first car-radios, and it was from this ... humming importantly under the dash ... that I heard the cobwebby voice of Chamberlain say "... and so this country is at war." (The house in the background of this photo was the home of my friend Percy, 70 years later he is a retired New York doctor with whom I swap emails and occasional MP3's of our current jazz enthusiasms.)

One of Britain's celebrities throughout the war was

the man who broadcast a few physical exercises every morning. So familiar

were his stock phrases that they were regularly lampooned by comedians.

He was Captain Coleman-Smith, late of the Indian Army and, during our years at

Glasgow Academy, our Gym Master. (How sad that Coley appears nowhere in

the first 50 results of a Google search.) Much later, when he retired, he

bought the lodge on Inchmurrin and passed the rest of his days peacefully there.

Every four years our fellow Macleans from all

over the world gather at the Chief's castle, Duart, on the Hebridean isle of

Mull (a few years ago they were so kind as to elect me first International

President of their twelve territorial Associations). Usually Ann and I

fly to Glasgow and rent a car for the 100 mile run to the ferry at Oban, but

last time we made the journey as my parents used to do it - on the overnight

sleeper train to Glasgow, then to the ferry by the scenic railway

line. I had, I confess, waxed a wee thing lyrical about the views to be

savoured running up the West side of Loch Lomond through Luss and Ardlui

... so it was disappointing to find that the track is now so

overgrown that we had to shut the ventilator-windows because we were being

showered with leaves - and the majestic vistas were rarely visible through the

foliage.

In 1943 I reached 17 and enlisted. As I recounted in an earlier blog, after initial training as an Air Force pilot, I transferred to the new technology corps REME and began a long period of training.

In 1944 my father concluded a review of the structure of his biscuit division with the recommendation that it be integrated with another division and that his role be ended. (An earlier paragraph of that Chairman's letter praises his integrity in doing this.)

In my brief home-leaves I remember sensing his deep unease at being, for the first time, unemployed - a sensitive and emotional man, that letter sustained him in his search for a new role. Which turned out to be as CEO of an old-established maker of decorative tins, with plants in the English Midlands, and which had just been acquired by the mighty Metal Box Company.

And so my parents left Scotland for their new home near Nottingham. The London house having been called 'Duart' they named this house 'Lochbuie' after another significant Maclean location on the Isle of Mull.

|

|

1945 Mansfield, Notts |

My brother finished his schooling at Glasgow

Academy as a boarder - under the supervision of "Coley" and his wife - before

joining our parents at Mansfield. Sister Deirdre was by now at her

boarding-school, Polam Hall, near Darlington. I spent occasional

weekend-leaves at Mansfield - feeling the difference between my dull life as a

military student at 'Wandsworth Tech' and the life Nigel was briefly enjoying

with a copious supply of glamorous partners on the tennis courts at Lochbuie.

Dad took me to see his new factory at nearby Chesterfield - showing me the ramps where lorries offloaded tons of sheet metal and, at the other end of the plant, similar ramps where a stream of lorries collected millions of "open top" food cans.

But my main recollection of Mansfield weekends is of the droning

crescendo in the evening sky as it gradually filled with clouds of RAF bombers

assembling for their awesome forays over Europe.

Nigel joined a Scottish regiment and quickly became an officer. To my dismay I found that not being a science graduate precluded my being commissioned in REME and so I contented myself with moving up the non-commissioned ranks (until, as the war ended, I was commissioned into Royal Signals.)

Late in the war I was assigned to a huge exhibition of captured enemy armaments. The devices I was given to demonstrate aroused much interest - they were Geiger-Counters - detectors of radio-activity. The explanation I was given - and which I uneasily dispensed - was that the enemy were now deploying mines made of plastic (and thus not showing-up on traditional metal-detectors). The story was that in order for the Germans, when necessary, to know where they were each one was buried with a small bag of 'tarn-sand' - a slightly radio-active mineral mined in Czecho-Slovakia - which they could locate with these Geiger-Counters.

Subsequently, like everyone else, I was awed by the news of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima & Nagasaki ... and - unlike everyone else - I had the "Eureka Moment" of realising the real purpose of those Geiger Counters.

In 1945 when at long last the war was over I was lucky enough to be in London, first for 'VE Day' (Victory in Europe, in May) and then 'VJ Day' (Victory over Japan, in August). I savoured the heady celebrations - the streets were thronged - like everyone else in uniform I roamed the West End being plied with cakes from Lyons Tea Shops and beer from pubs - and hugging and being hugged by all and sundry.

|

|

1952 Linby, Sherwood Forest |

When my 'demob group' ("60") came up I was told,

to my chagrin, that I must stay on to complete the lengthy training of the

small group of engineers whose responsibilities included secret cypher

systems. This, and the consequently greater risk of being recalled in

future, persuaded me to transfer from REME to a special Squadron of Royal

Signals. Ironically this ensured that I WAS recalled ten years later for

the "Suez" escapade! Which will be the subject of a later blog.

When my parents retired they bought this house on the edge of Sherwood Forest. I visited it only once and found it rather prim and tidy - I much preferred the 'lived-in' atmosphere of all our previous homes.

S

adly my father's WW1 injuries were beginning to take their toll and his health deteriorated so that, when they decided to move to rural Essex I took a week's holiday from the BBC and accompanied my mother in her house-hunt.

We looked at some beautiful houses in lovely

villages with names like "Steeple Bumpstead" but it was on the edge of the

historic town of Great Dunmow that we found "Portways" - the

300-yr-old

home where my parents, as always surrounded by friends, (and dogs), wrote the final

chapter of their energetic life.

|

|

D.H.M.

- - - - -

- - - - - -

Back to 'Contents' table

On to Blog 7

- - - - - -